Different Discussions

Along with the loss of the sense of self has gone a loss of our language for communicating deeply personal meanings to each other. This is one important side of the loneliness now experienced by people in the Western world.

Rollo May, Man’s Search for Himself.

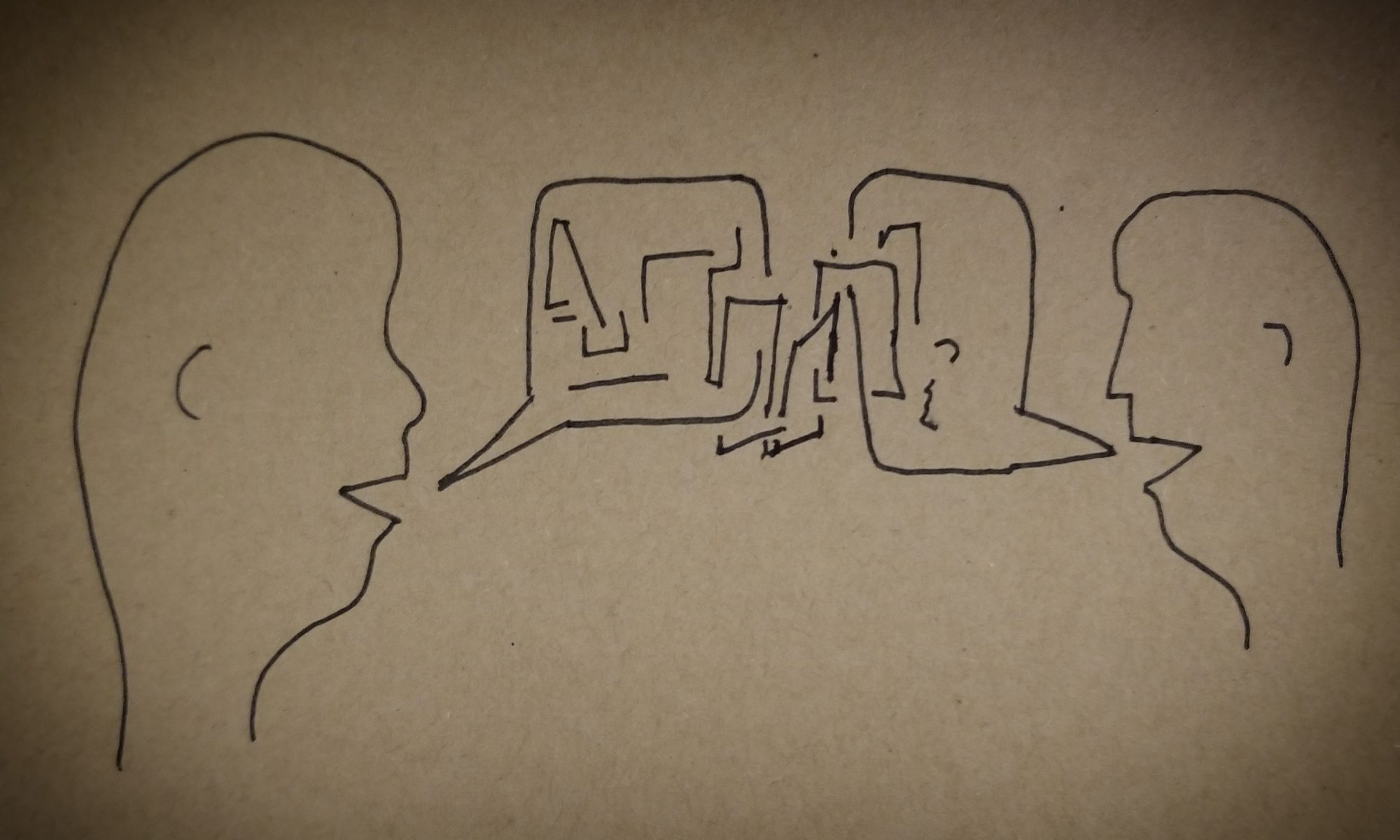

One of the most frequent requests in couples therapy is help with communication. Over the years, I’ve noticed that most conversations in relationships fall into three general categories: Debates, Dialogues, or Dialectics. I don’t think either of these types are inherently bad or good. However, some are more beneficial than others in different situations, so it’s important to know what type of communication you’re having! Without that, who knows if your conversation is moving you in the direction you want?

Debates

God Can’t: A Review

― Soren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling

Overview:

Dr. Oord has answered these questions through multiple publications on love (The most recent of which are: The Uncontrolling Love of God, Uncontrolling Love, and God Can’t). For Oord, freewill is a necessary condition of God’s love for us; an “Essential Kenosis” (EK). What this book adds to the already published works is a teleological application of the theological concepts. It’s one thing to talk about a general “trauma” and to offer platitudes like, “God works in mysterious ways”. That may be, but that doesn’t mean God is illogical, chaotic, capricious, and flippant. If we take seriously the idea that God is love, we must also take seriously the pain and suffering in the world.

God Can’t explores the idea of EK, the existence of trauma (evil), and how we can respond. If you read this book, you take a big risk. You may have to accept genuine responsibility. And that’s not something everyone is willing, or ready, to do.

Responsibility:

Many therapeutic conversations work to distinguish the difference between fault and responsibility. Fault is about blame; who did what to whom, and when. Responsibility is about response: our ability to respond to a situation. We are not always completely at fault. We are always 100% responsible for how we respond. I have written about this in the past, but Yalom defined responsibility like this:

“To be aware of responsibility is to be aware of creating one’s own self, destiny, life predicament, feelings and, if such be the case, one’s own suffering. For the patient who will not accept such responsibility, who persists in blaming others — either other individuals or other forces — for his or her dysphoria, no real therapy is possible”.

What does this mean for those who have experienced trauma? It means so many things, but I am going to break it down into 3 sections: Be, Do, Have. The BDH model has been around so long, I can’t find out where it came from, but there’s a great explanation here: Be Do Have. Briefly explained, BDH is the idea that we must first know who we are (Be), and allow that to inform our behaviors/decisions (Do), and commit to altering and changing our actions until we get what we are working for (Have). The problem happens when we start with what we think we want (Have), then work and stress (Do) to try and get it so that we feel validated/ “ok” (Be). This process makes the security of our personhood dependent on outcomes and what we own. That externalization of self turns small threats into massive, existential, threats about our very being!

Be

Personal Punching Bag

At intake, the couple described a sense of all the air being sucked out of the room. X’s offhanded comment had resulted in an emotionally cold and distant response from Y. Y looked directly at X and, with absolute conviction, stated, “I knew you’d do this. I just didn’t think it’d be so soon.” X was flabbergasted! Clarification was requested, but Y walked out of the house without stating an intended destination or time of return. X, alone in the house, chose to watch some TV, clean a bit, but more than anything, functioned in a fog. It wasn’t until late that evening when Y returned home; still cold and aloof. X gave Y some space, hoping this would offer some appeasement. After a long and silent dinner, as bedtime approached, there seemed to be no relief in the tension. As the couple drifted off into the fitful sleep only emotional exhaustion can foster, Y began to shout and cry while sleeping. Y flailed out with their arms, then drifted back into silent sleep. Naturally, this had upset X, who also slept in small spurts, punctuated by the sounds and movements of Y.

The next morning, though tired, the gravity of the situation had seemed to reduce. Y was in a better mood, had smiled at and even hugged X, and had left for work as normal. X breathed a sigh of relief and returned to a regular routine. Things seemed to be getting better, but over the next few weeks X noticed Y was working longer hours, often not returning home until late at night, well after their usual bedtime. Physical intimacy decreased to zero and, when questioned by X, Y become very hostile and angry. X attempted to clarify the concern regarding their intimacy. Y responded defensively citing exhaustion from an increased work-load, accused X of not appreciating how hard Y was working, and would often disappear for several hours after these discussions.

During the interview, Y regularly looked surprised as X recounted many of their interactions. Y claimed to remember fewer than half of these discussions and sat through the majority of the session avoiding eye contact, with closed body posture, and minimal participation. X was the primary agonist for pursuing therapy and was the most verbal historian at intake.

Now let’s explore how the potential ePTSD reactions could be expressed (1-4) and a few interventions (responses) the existential therapist may use to encourage meaningful healing. Many of these symptoms may overlap at various points. This is common in working with families and individuals dealing with trauma.