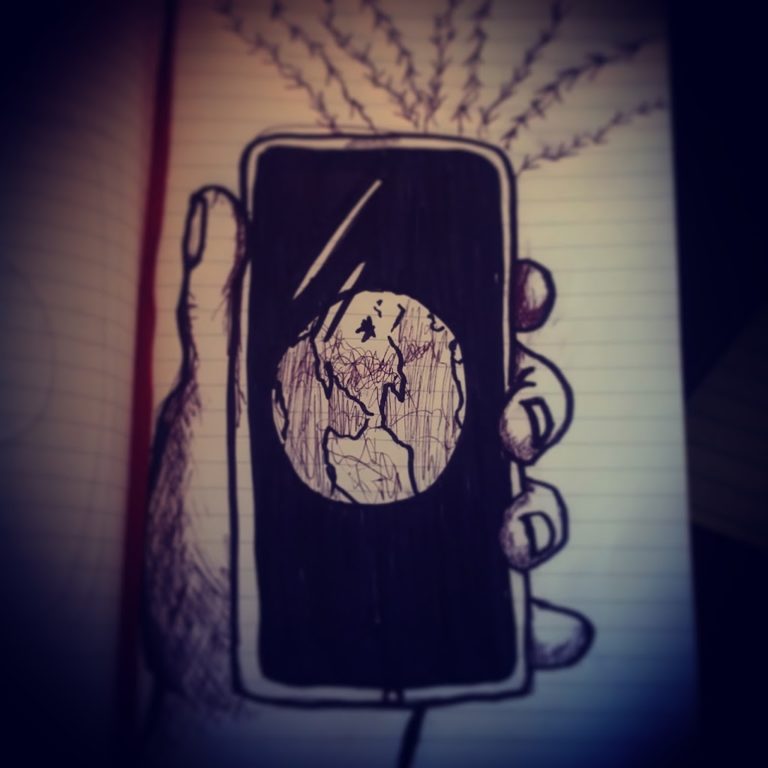

Mobile ExCommunication: Keeping Tech in Check

“Freedom is thus not the opposite to determinism. Freedom is the individual’s capacity to know that he is the determined one, to pause between stimulus and response and thus to throw his weight, however slight it may be, on the…