Love: Part D of 4.

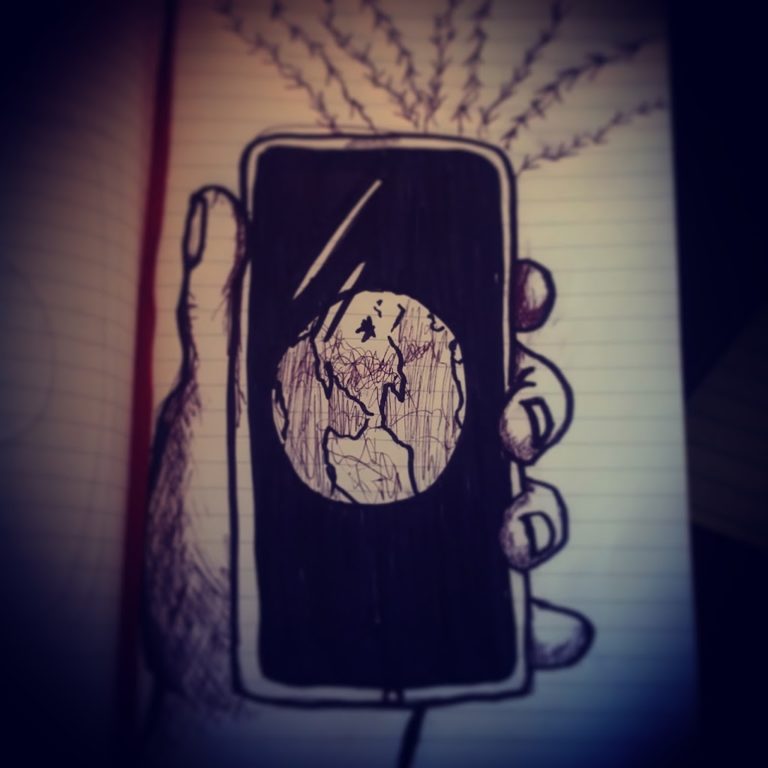

Our lives are slipping away. In minutes and by seconds, our lives are taken from us. We have no say in this. We do, however, have a say on what we spend our time. Really, that is the only…

Our lives are slipping away. In minutes and by seconds, our lives are taken from us. We have no say in this. We do, however, have a say on what we spend our time. Really, that is the only…

“Play makes us nimble — neurobiologically, mentally, behaviorally — capable of adapting to a rapidly evolving world.” ~Hara Estroff Marano: A Nation of Wimps I’ve heard discussions about something called the Buddy Bench. These are benches for children to…

“Freedom is thus not the opposite to determinism. Freedom is the individual’s capacity to know that he is the determined one, to pause between stimulus and response and thus to throw his weight, however slight it may be, on the…

“All real living is meeting.” ― Martin Buber, I and Thou In providing marriage and family therapy, we almost always come to an issue of trust. How do we restore broken trust, how do we maintain healthy trust, and what…

“Your perspective on life comes from the cage you were held captive in.” ― Shannon L. Alder Introduction The first post provided a brief overview of BPD by way of metaphor. Now, I would like to suggest an original way of…