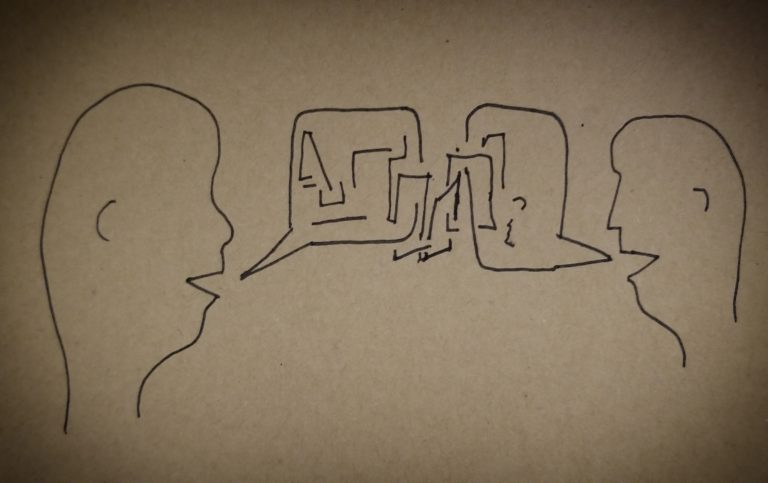

Different Discussions

Along with the loss of the sense of self has gone a loss of our language for communicating deeply personal meanings to each other. This is one important side of the loneliness now experienced by people in the Western world.…

Personal Punching Bag

“Most people have no imagination. If they could imagine the sufferings of others, they would not make them suffer so.” ― Anna Funder, All That I Am Personal Punching Bag The majority of clients and families I have…

It’s OK to Still Like Pulp Fiction

Not Necessarily Truth.

“I remember driving to therapy and thinking, ‘Well, this is it. I’m all out of stories’. I didn’t know what I was going to say. And that was when therapy really began.” -Dr. Ron Wright on attending therapy while in…